Alexander von Humboldt: A Naturalist Between Legend and Truth

28 February 2019

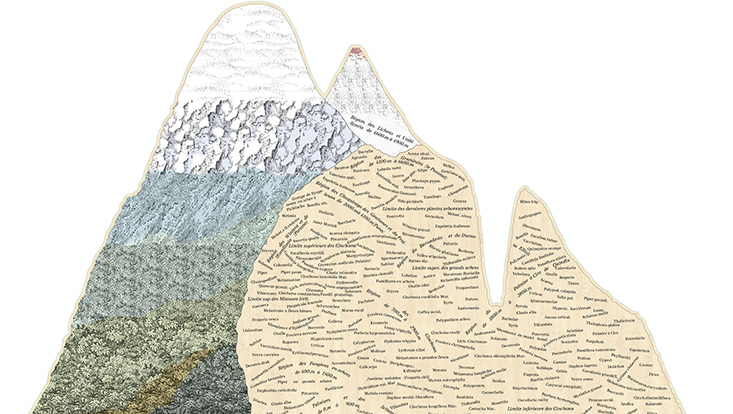

Photo: „Naturgemälde der Anden“, Tübingen, J.G. Cotta 1807

In his "Natural Painting of the Andes" with Chimborazo, Humboldt records the climate and vegetation stages - a modern infographic.

Alexander von Humboldt was already a legend during his lifetime. He was a dazzling personality and an artist of self-dramatization. Even though his scientific work is unique, posterity has often exaggerated the German naturalist in heroic terms. The curators of "Animals in the Tropics" in our upcoming special exhibition "Humboldt Lives!" look at how much truth there is behind the myth. Author Peter Korneffel tracks down Humboldt in Hamburg, and Matthias Glaubrecht questions his role as a "world star of science".

Oh, so Humboldt is alive?

Peter Korneffel:

Humboldt lived longer and louder than anyone in Hamburg would have believed. Here in the Hamburg Stock Exchange Hall, he was declared dead on June 12, 1804. It was written in black and white in the "Hamburger Correspondent" that Humboldt, who was so eagerly awaited back from his trip to America, had suddenly died of yellow fever in Acapulco. Fortunately, the Hamburgers were mistaken: Humboldt is alive! And we will now show you how he lives on in us today.

So what did Humboldt have to do with Hamburg?

Peter Korneffel:

Quite a lot. His ambitious and broad education included, to a large extent, his studies at the private commercial academy in Hamburg. Here he spent eight months learning business and empiricism from the famous Johann Georg Büsch. Humboldt himself found this stay "pleasant and instructive". Hamburg bankers then helped Joseph Mendelssohn eight years later to convince the King of Spain of Humboldt's financial independence. And, of course, Humboldt repeatedly sent collections from America via Hamburg.

It is always assumed that Humboldt was the forerunner of Darwin. How do you see that as an evolutionary biologist?

Matthias Glaubrecht:

Humboldt tried to survey the world and gather all the data and facts about its nature. Yet he himself is much less of an "explorer" than has long been assumed. He is neither the "second discoverer of South America" nor a pioneer of the theory of evolution by selection developed decades later by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Humboldt's understanding of nature was superseded by Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859, the year of his death at the latest.

Humboldt did not develop any regularity from his measurements and observations. Darwin, on the other hand, went beyond mere description and speculation. We owe him profound insights. For example, that living nature is not in equilibrium but in constant upheaval, just like the entire globe and the universe itself.

What is Humboldt's significance for zoology?

Matthias Glaubrecht:

Actually, we have to state that observation and records, observations and measurements on site during the journeys form the foundation for Humboldt's later research and publications much more than his collections of natural objects.

Humboldt documented his zoological findings in drawings that have received little attention to date - we are showing some of these truly impressive works in our exhibition - along with objects he saw at the time. However, many of his specimens from South America were lost on the journey or lie today, mostly unrecognized, in various collections in Europe.

Can Humboldt be called the founder of ecology? What was new about his view of nature?

Matthias Glaubrecht:

With the "Nature Painting of the Andes" - the well-known cross-section of the Andes profile with horizontally staggered vegetation zones - Alexander von Humboldt popularized plant geography and contributed to the later founding of ecology. He is a mastermind of ecology long before the term itself was coined (in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel as the doctrine of the household of nature).

By conceiving of nature as a cosmos in which everything from the tiniest to the largest is interconnected, he laid the foundation for our current understanding of an interconnected environment.

However, Humboldt was ultimately far less modern and progressive than previously believed. His idea of a harmoniously ordered cosmos and a nature oriented towards beauty and balance are ultimately rooted in occidental thinking stemming from antiquity and a romanticism of the late 18th century that was also influenced by Goethe and Schiller, among others.

How did Humboldt do his research? What was it like to travel as a scientist at that time?

Peter Korneffel:

Humboldt was a "driven man," as he himself said, full of longing for the tropics. He was young, diversely educated, empathetic and hardly restrained in his urge for the "great and good". Thanks to his family's handsome inheritance, he was able to buy the latest instruments and finance the great journey himself. He was obsessed with measuring and obsessed with observing. Through this he wanted to understand and put things - he meant all things - together. Nevertheless, the trip to America was in large parts improvisation and a highly risky undertaking. It borders on a miracle that he survived it.

For whom is the exhibition interesting?

Peter Korneffel:

For everyone who believes that everything in our world does not yet fit together, or no longer does, and who trusts this sometimes somewhat loopy natural and cultural researcher Alexander von Humboldt to be able to shed some light on it even today.

More about the exhibition in the Museum of Nature Hamburg - Zoology, Botanical Garden and Loki Schmidt House:

https://www.cenak.uni-hamburg.de/ausstellungen/museum-zoologie/humboldt-lebt.html