Influence of permanent eggs on the population genetics of branchiopoder crustaceans

Branchiopod crustaceans reproduce with the help of special drought-resistant permanent eggs. These permanent eggs can survive for years and even decades in the sediment of dried-up temporary water bodies. When the water bodies fill up with water again, the permanent eggs hatch and thus form a new generation and local population. However, not all permanent eggs hatch in the same wet period, as this would quickly lead to the extinction of the local population in the case of a very short wet period. Thus, permanent eggs of many generations accumulate in the sediment and form a so-called permanent egg bank. This permanent egg bank has profound population genetic implications, because each new generation (clearly separated in time from the previous one by the preceding dry period) consists of the direct descendants of a large number of earlier generations: Permanent eggs laid by different earlier generations hatch at the same time and thus lead to a mixing of otherwise clearly separated generations in terms of time and reproduction. Thus, for example, genetic lines that were not present in the adult populations of a water body for years can reappear through the hatching of "old" permanent eggs without the need for immigration from neighbouring water bodies. The extent to which this actually influences population genetic processes and has an impact on the interpretation of phylogeographic processes, for example, is still largely unknown. Initial studies on spinicaudate crayfish (Limnadopsis parvispinus and Paralimnadia sp.) in the Australian deserts have shown that some populations have a very high genetic diversity and that the genetic composition differs greatly between years (or generations). Thus, a large number of haplotypes could only be detected in one year.

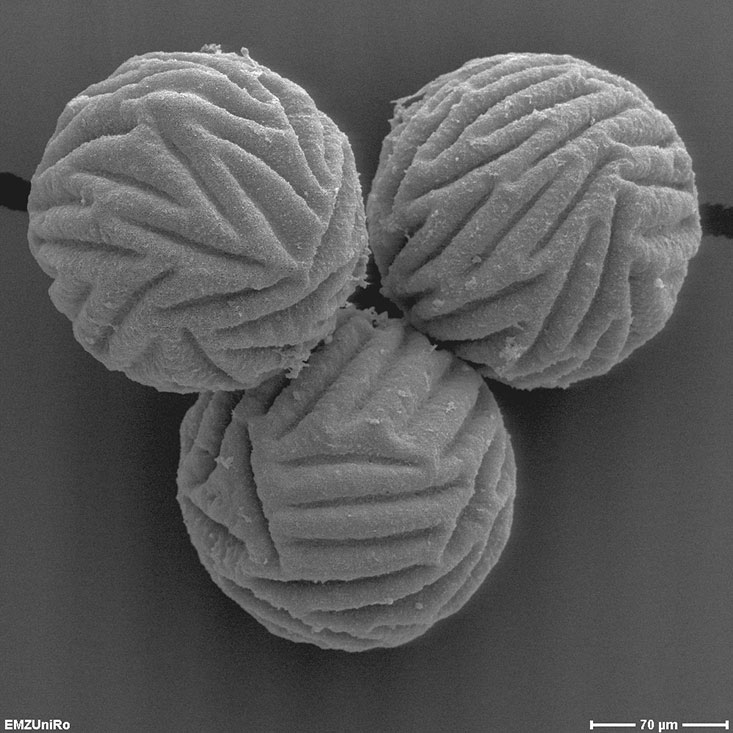

Figure: COI haplotype network of individuals from successive generations of a water body.

Future studies will, on the one hand, include a larger number of individuals and generations. Secondly, by using ddRADSeq instead of sequencing a single gene (COI), hundreds or thousands of genomic markers will be analysed in parallel. This allows a much more detailed tracing of whether successive populations are directly descended from each other, or whether the hatching of 'older' permanent eggs predominates. Furthermore, it can be investigated whether genetic differences between generations are mainly due to stochastic processes or to selection (e.g. due to different ecological conditions at the time of hatching).

Selected publications:

-

Schwentner, M., Richter, S. (2015): Stochastic effects associated with resting egg banks lead to genetically differentiated active populations in large branchiopods from temporary water bodies. Hydrobiologia 760: 239-253.

Lectures and posters:

-

Schwentner, M., Richter, S. (2014) ‘The impact of resting egg banks and temporal dispersal on year-to-year changes in the genetic composition of adult populations and population differentiation in Spinicaudata (Branchiopoda).’ 8th International Crustacean Congress 2014 in Frankfurt a. M., Vortrag