Treasure of the month: dating under power

2 August 2019

Photo: UHH/CeNak, Möckel

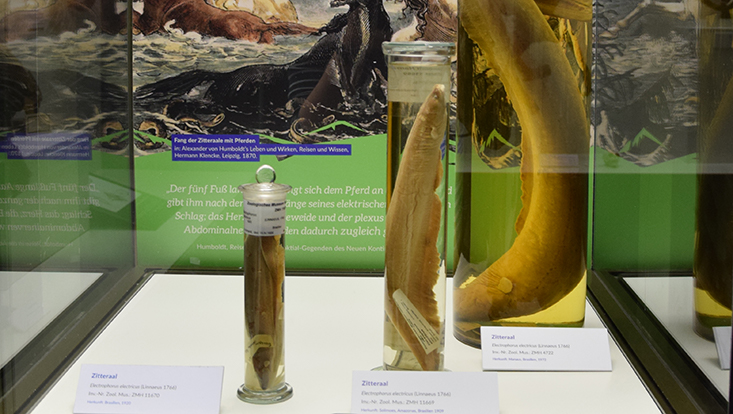

The electric eels from the Ichthyological Collection in the special exhibition "Humboldt Lives!"

"After experimenting on them for four hours, we felt muscle weakness, pain in the joints, general nausea until the other day," wrote Alexander von Humboldt about one of the strangest animals on his South American expedition. At LIB, the fish, whose defensive behavior is not the only thing that is electrifying, is at home in the Ichthyological Collection: the electric eel is our Treasure of the Month for August.

Dramatic events took place in the swamps of Venezuela in March 1800: electric eels sprang up from the water on horses and mules that had been driven into the water, electrocuting the animals. Two horses became unconscious and sank. At least that is what Alexander von Humboldt wrote, for whom the natives were supposed to catch live electric eels. His account of the trip says: "Namely, the noise caused by the pounding of the horses frightens the electric eels out of the mud and incites them to fight back; they swim to the surface of the water and force themselves under the belly of the horses and mules." A few exhausted electric eels were finally able to be examined by Humboldt and his companions.

At home in northern South America

But the electric eel is not an eel at all. "The species belongs to the New World knifefish, which have as common characteristics a very long anal fin running almost over the entire body and electric organs," explains CeNak fish expert Ralf Thiel. The body of Electrophorus electricus, which can reach up to 2.50 meters in length, consists largely of muscle tissue that has been transformed into electrical organs. Muddy and oxygen-poor freshwater habitats in northern South America are its habitat. With its dark gray, gray-brown or black-brown coloring, the animal is almost reminiscent of military nuclear submarines; relatively small eyes sit above the wide mouth.

No exaggerations

While Humboldt's descriptions were long considered exaggerations, recent experiments show that the animals can actually catapult themselves out of the water. In doing so, they press their head (positive pole) and the tip of their tail (negative pole) against potential attackers or prey and deliver electric shocks. The electric shocks are conducted directly into the target through contact. And the farther the animals speed out of the water, the higher the measured current and voltage. Such attacks are effective because underwater the fired current is evenly distributed in all directions.

Protected from the electric shocks

The voltage generated in this species is so high that the fish can also use it to kill prey - mainly other fish. Using a nerve signal, the electric eel can interconnect its organs like battery cells, firing up to 860 volts into the environment for short periods of time. "The electric eel's vital organs, located in the front part of the body, are protected from the electric shocks by an insulating film of mucus on the skin and additional layers of fat," says Ralf Thiel. Eight electric eels are archived in CeNak's ichthyological collection, which is one of the most important in Germany with more than 8,000 fish species. "The specimens come from Brazil and entered our collection between 1887 and 1972," explains researcher Thiel. The wet specimens are stored in 70 percent ethanol.

Searching for partners with electrical impulses

While, according to Humboldt's descriptions, Humboldt and his companions spent days examining the fish they caught, the animals even use their electrical impulses to search for a mate among themselves. In the murky muddy water, potential mates are attracted to each other by the electrical impulses. However, the electric pulses emitted are quite weak. Electrophorus electricus mainly uses its electrical abilities to defend itself against enemies, to define its territory and to orientate itself in the water, as its sense of sight is only moderately developed. After mating, the males build nests of aquatic plants and later guard the eggs and larvae. These are just ten millimeters long when the fascinating "electric fish" hatch.

Further information